Multiple

Sclerosis: a disease in which the immune system eats away at the protective

covering of nerves

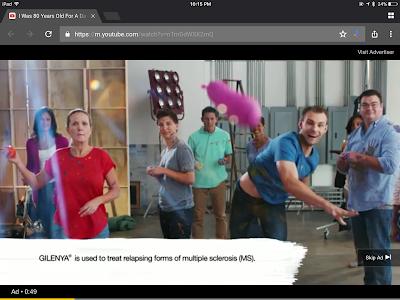

I was watching a Buzzfeed video (yes,

I know I should not become addicted to these videos) and there was an ad

playing about multiple sclerosis. I normally just try to skip the ad as fast

as possible because I want to watch the video. However, after further thought, this

action—adopted by almost everyone—is a signal of our rejection of viewing

chronic illnesses. We are not interested in learning about a disease that many people

around the world suffer. Yet, the commercials are also at fault. If you look

below, the images show happy, active people who look perfectly “normal.” It is

as if this magical medication was able to cure their illness and keep their

nervous system intact. Not to mention, the last photo states, “real people,

real stories.” If the ad is truly a demonstration of people who suffer from

multiple sclerosis, why do none of people have a slight motor disability? Sure,

a drug can slow down the progression of the disease and alleviate a few

symptoms, but the people would still have some issues—including the side

effects the lady on the picture seems happy about.

People who are initially diagnosed with

this degenerative disease are told the same facts: there are no cures, there

are only treatments to help alleviate symptoms, you will end up in a

wheelchair, and you will live until your imminent death. Not only do these

people come to the salient realization that their future will not be what they

imagined, but they also have to deal with the physical and emotional abuse

society throws towards them. Scathing remarks—cripple—are precariously used to

describe people with disabilities, causing a feeling of inadequacy; they compare

themselves and see only the ideal body types being displayed. While “normal”

people may have surgery done to enhance their appearances, disabled people

cannot escape it. They cannot hide from society and mask who they are: they are

thrown into a society that neglects the need for accessible facilities. Take

Troy High School for example. The hallways are far too crowded to give students

on wheelchairs space to maneuver; the defunct elevator moves at a snail’s pace,

almost suggesting that getting to the students’ destination in a timely manner

is not important; the classrooms have tables that are too high to reach.

Furthermore, this daily struggle is

not simply faced during their childhood—it is a continuous cycle that they must

face. I recently watched What Would You

Do? and how deaf discrimination pays a roll in job employment. The show set

up a scenario where a manager openly said that he would not accept the deaf

girl’s application. As with most episodes, there are always many Samaritans who

object the injustice presented. However, only one man brought himself to go

against the manager’s judgement, stating that rejecting an application based on

a disability is outright discriminatory. Not to mention, there were several

human resource workers who not only supported the manager’s decision, but also

gave him advice on how to handle the situation better: accept the application

but write a note reminding yourself that the applicant is “unfit.”

Our society is not just unaccustomed to seeing disabled people, but it believes that these people are not inherently equal to everyone else. As Mairs states, “for the disable person, these include self-degradation and a subtle kind of self-alienation not unlike that experience by other minorities” (14). Although many people with disabilities are able to come to terms with their body, many still struggle with internal hatred: the belief that they are not as valuable and are the rejects of society.